Social media platforms which allow for others to capitalize on your content breed unhealthy behavior. The more prominent other people’s (potentially unwanted) content features in your spaces, the greater the incentive there is for misbehavior at the individual level. In this way, Twitter’s platform behaves in a fundamentally different way from other social media platforms, by allowing any individual to force themselves into your space without a way to eliminate that risk. Platforms have a responsibility to find ways to improve their social spaces, and providing greater control is often the first step.

Twitter and the Wild West of Threads

The primary way that Twitter users can “take up space” in the social space of other users is via replies. Since the introduction of the conversationl view in 2013, replies are displayed prominently, based on an ordering that seems to generally be centered around some form of popularity or engagement.

For users with non-locked timelines, ths effectively means that every tweet on the platform creates an opportunity for any user to share their own content in these shared social spaces. The sorting within this space means that users with large follower-bases will tend to rise to the top of the displayed replies. At this point, on any popular and controversial tweet one of the high-ranked responses will likely come from someone who disagrees with the author strongly. These high-ranking replies will likely be exposed across the plataform to many of the people who agree with them – along with showing them the original content, in a way that makes it easy to jump on board with their own reply.

In many cases, of course, this type of behavior is benign, or even positive: more than once, I’ve established new connections with coworkers, gotten feedback that helped me improve my knowledge, or simply been buoyed up by social support from these comments. Twitter is designed, as a platform, to expose users of the platform to broad range of content the folks they follow interact with, and when the interactions are positive, the results can produce positive results. However, the downsides can be enormous. A single reply can drive hundreds or thousands of reactions – and each reaction can set off its own chain reaction. In many cases, a controversial reply will drive more engagement than the original post did.

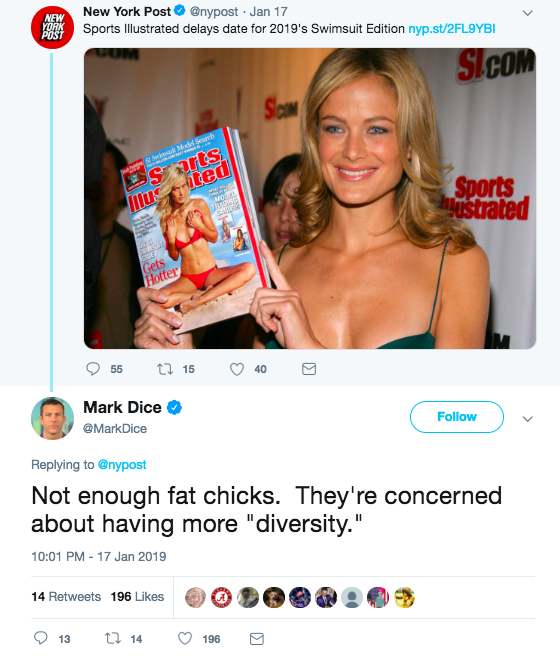

In this case, an insulting reply drives significantly more engagement than the initial post.

There’s no way to limit who can share your content – for example, marking your content so that only followers have the ability to reply – so a single reply from a popular account can lead to days or weeks of ongoing harassment as it makes its way around the social network of that person.

The fundamental way that Twitter is different than most other social networks is that there is no way to remove content from the conversation view of your tweets, nor is there any way to detach a reply from the tweet to which it is replying. That is: on every other social media platform, content you post is your space, and you ultimately control that space. For example, if someone leaves a disgusting comment about how a photo looks on your Facebook timeline, you can remove the comment. That is not true on Twitter, where the replies to your tweets are considered part of the commons, usable by everyone to share whatever content they choose.

Fundamentally, this makes the replies to every tweet a shouting match. For popular controversial figures – think Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, or Donald Trump – these become forums for both supporters and detractors to hurl insults at the poster and at each other, in either case taking advantage of a platform with massive visibility to spread whatever message they think is important. It also has a tendency to reward “early” posters: because the ranking is strongly related to popularity measured by engagement metrics, early tweets are more likely to rank highly, as they have an opportunity to be seen by more folks early on, creating a cycle: “It’s at the top of the list because other people liked it, and other people liked it because it was the only thing in the list.”

With 2000 followers on Twitter, the typical tweet I make on my own timeline will receive 300-600 impressions. A tweet in response to something popular can receive thousands, or tens of thousands, even for a relatively benign response. One example: a tweet I wrote in reply to an announcement of a new tool received 6900 impressions, with only 7 likes – because the tweet it was replying to received more than 8000 retweets. This single tweet also gained me two new followers – for effectively repeating what a dozen other people had already said. I was ‘rewarded’ (in a sense) for engaging with popular content.

In my case, that engagement was benign: maybe a bit repetitive, but at least not toxic. When that engagement is toxic, the effects can be multiplied: because controversial disagreements will tend to create additional responses, the effect is magnified: every time someone replies, or likes or shares a controversial reply, you’ll be expanding the network of people who are exposed to both sides of the disagreement – positive and negative. When Mark Dice replies to a left-leaning politician’s tweet calling them out, his entire audience is exposed to that. When someone replies to him to respond in kind, it will swing back in a different direction. While Twitter doesn’t show every reply from most of the folks you follow, every reply, retweet, or even like will expose the content to a broader audience, and there is nothing you can do about that as the original poster.

How did we get here?

Of course, this isn’t always the way Twitter’s platform behaved. A fundamental reason for the lack of control of “threads” as owned spaces is primarily because the platform was built without the intention of replies or conversations. Each tweet stood alone: while you had a timeline and mentions, there was initially no concept of anything like a reply.

Conversational tweets back and forth were a slow evolution. Replies – the use of an “@username” at the start of a Tweet – were not originally a built in feature, but rather just a way that users behaved on their own; Twitter later added some support for handling these elements in a better way, but still didn’t build social spaces around them. The first sign of this was when Twitter initially aded support for “conversations” in 2013.

Screenshot from Twitter’s announcement of Conversations.

The conversational view is the beginning of the social spaces around tweets: rather than each tweet being standalone, they were connected, creating a place where it would be possible to see the responses from others – both good and bad.

While conversations initially focused solely on cross-user communication, over time, users evolved to use the UI in other ways as well. Because of the how the UI worked, self-replies were a viable way to show further posts related to the first one. Over time, this evolved, with users replying to themselves in longer chunks in order to create “threads”: connecting their own tweets together to create longer form text. The first official support for threads came in late 2017, with Twitter adding the ability to tie multiple tweets together when posting as well as introducing the “Show this Thread” UI element to make existing threads more obvious. These changes expanded the Twitter UI’s support for conversations as social spaces where the creator of the thread has some ownership, but where active participation is exposed to a broader audience.

These evolutions – initially conversations, and later threads – turned tweets from standalone elements into a shared social space. With these evolutions, there has been no increase in control to the owner of the social space: These changes allow third parties to take advantage of the platform of others, but without any of the tools to limit the negative side effects of these decisions.

Threads aren’t the only way that Twitter’s evolution has shifted to allow for more disruptive conversations. Originally, Twitter used to provide options as to whether you wanted to see replies directed towards people you did not follow in your timeline. A 2008 post in the Twitter blog explains that “You should feel free to @reply people and not worry about it being out of context to some of your followers. In general, they won’t see it.” At the time, Evan Williams indicated that his preference was to remove the option to see replies directed towards others entirely: “my preference is to take out the setting altogether and just make it work like the default”. Obviously, this has changed since: while it’s still typical that you won’t see every reply someone makes, many of them will show up on your timeline, with no ability to disable that behavior.

I follow Weather is Happening, but not Donald Trump – but Trump’s content is displayed in my timeline anyway due to this reply.

Over time, replies have become a more broadly encouraged style of tweeting as well. As part of a move to encourage more user-to-user communication, in 2016, Twitter made an announcement that they were making changes to make replies easier to understand, and encourage the use of them, as detailed in a New York Times article about @replies no longer counting towards the character count. At the time, Mike Isaac wrote “The adjustments amount to the biggest makeover to the form of a tweet in years.”

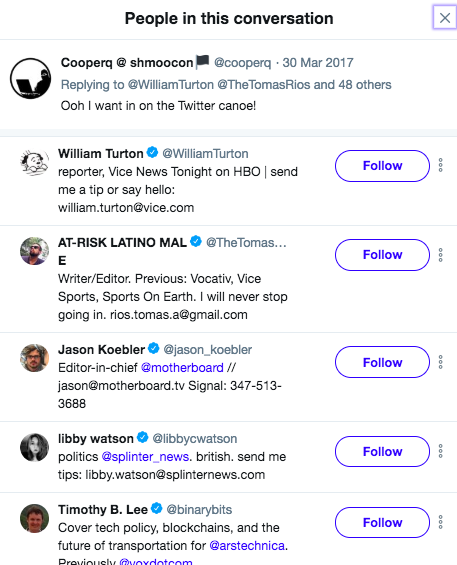

That change – which didn’t end up launching for everyone until March of the following year – ended up changing not only the character limits on Tweets, but also the way replies are displayed and how multi-person conversations work. Counting usernames towards the character count limit had a meaningful and practical effect on how big any particular conversation could be on Twitter: every person added to the conversation would count against your 140 character limit, shrinking the amount of space you could type in any given tweet, and encouraging conversations to take place in small groups. The tweet text would always have the name of every participant in it, so you always knew exactly who you were talking to. When the change to usernames rolled out, that UI changed entirely: rather than including the names of the people you’re replying to in the tweet body, they were included in a separate UI widget, and up to 50 people could be included.

On the launch of the reply changes, several threads used the feature to its fullest, creating long-reply chains including the 50-participant maximum, like this tweet from cooperq.

A Vox article referred to these large multi-person conversations as ‘Twitter canoes’. Prior to the change, you would occasionally get into large multi-person conversations, but afterwards, this simply became the norm: rather than directing your tweets to a narrow, limited audience, the default is to just “reply to all”.

Where Are We Now?

Through the slow evolution of their social features, Twitter has created an environment where authors now own social spaces they can not control. Twitter initially created these social spaces in 2013 with the introduction of the conversations feature, but added no meaningful access controls for the creators of these spaces. Users used these new spaces to post ever longer content – eventually evolving to full essays provided in bite-sized chunks – turning them even more into personalized spaces and eventually the creation of the thread as an officially sanctioned usage of the platform. Twitter evolved replies to expand the number of people who could be included in any conversation. And through all this, they provided almost no additional controls for tweet authors to control their space.

This evolution has many positive effects: many of my favorite accounts on Twitter are heavy users of these features, and I have collected hundreds or thousands of interesting threads over the years from authors who experience Twitter as a great way to share their knowledge and experience. However, as with any social space, there are positives and negatives. With Twitter offering no additional controls over these spaces, they become a wild west, littered with everything from self-promotion to wanton abuse, with the creators of these spaces powerless to stop it. These fundamental choices about lack of control are consistent with Twitter’s apparent position that all tweets are effectively a part of the commons: that these social spaces are not owned by anyone, but shared for all.

The choice to treat everything which is said as a part of the commons is fundamentally flawed when looking at it from a perspective of harassment. Creating a social space without providing ownership is inadequate in a world where communities have different stanards they would choose to apply. We’re currently 9273 days into the September That Never Ended: The internet is no longer a social space where we can expect people to learn that their behavior is wrong and correct for it (if, in fact, such a thing ever existed). Social platforms have a responsibility to provide appropriate controls when they create social spaces, and those who choose not to create environments which disproportionately penalize targets of harassment.