Last week, Schuyler and I wrote TileCache, a WMS-C server implementation. OpenLayers is already a WMS-C client, so combining the two gives you a super-fast loading slippy map.

Yesterday, we wandered around town doing various thought experiments as to how to create a distributed peer to peer tile caching network. TileCache supports an extensible Cache plugin backend: any type of storage can be used. We wrote a simple Disk based cache, and also included support for a memory-based cache, based on memcached. The former is good when you have lots of disk, and a slow remote service. The latter is good when you need an LRU cache of the most important areas, but can fall back to the source data for everything else: simply install memcached, get it running, and the MemoryCache will do you fine with the defaults.

However, for things like landsat, most people don’t have enough disk to cache even the hot areas, if you plan to actually create a service which is usable. All of landsat as source data ranges into the terabytes, and even a just-in-time cache is probably on the hundreds of gigabytes scale: bigger than most people have disk for. (I’m biased in this sense: because I work for MetaCarta Labs, I do get access to some pretty sweet hardware. However, I try to target the things that we release to the more casual user, and in that sense, I look at my hosted webserver, which has an 80GB drive that I have full use of.)

So, we need a cache plugin which distributes caches to peers in a network. Ideally, because peers go down, you want to distribute the cache to multiple peers. You want the number of peers to be able to scale, and you want the changing of the peer list to not result in a complete load redistribution. (Apparently a term for this is ‘consistent hashing’, as described in this paper.)

While discussing that, Schuyler mentioned Chris Holmes’s post on S3 for secondary storage of tiles. Although in some cases this might make sense, I’m not sure that it does in the case of caching open data under the umbrella of OSGeo, which is the large part of why I’m thinking about doing this. For small data sources — the NYC Freemap, or the Boston Freemap — I can do local caches without running out of disk. For larger data sources, most of the important ones — like TIGER, or Landsat — could presumably be hosted under some form of OSGeo umbrella. If that’s the case, then falling back to S3 doesn’t make sense, since Telascience has offered very large amounts of disk space — larger than could reasonably be paid for on a monthly basis via S3. If you take the several terabytes available there currently, and do the math, you find that you’re looking at a cost of hundreds of dollars a month just for storage, and that’s before you even start counting the bandwidth costs.

I don’t know the exact particulars of the S3 service interface. It seems like it’s likely to be a key-based data storage system. Given the resources made available for exploring high-bandwidth, high-use applications for open geospatial work, I think that it’s much more likely that creating an S3-like service on top of the Telascience resources would be approved by the SAC than paying thousands of dollars per year for S3 storage and bandwidth.

I haven’t been able to think of a situation where using S3 would help me to muster the resources I need to solve a particular goal as the best solution. Perhaps if you don’t have machines that you can put extra disks in, it makes the most sense to go the S3 route, but I think that by the time you’re hosting such large datasets that you need something like S3, you’ve gone beyond cost effectiveness, given the resources available to most of the people participating in Open GeoSpatial Foundation, both personally and via other services made available for projects under that guise.

Of course, adamhill from the WorldWind project has reported that a just-in-time cache of 8 or so layers for the entire world tops out at about a terabyte for them. So perhaps that entire discussion is moot: most services are not going to have a serious problem with caching all the data they need. But when you need to scale to the level that Google does, you do need to investigate more serious services: but at that point, you better be making some serious cash, or you’re going to run into trouble at some point or another no matter what.

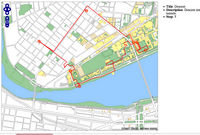

Went out for a late night walk tonight: though my path was a bit unclear, I think I made a decently accurate map:

Went out for a late night walk tonight: though my path was a bit unclear, I think I made a decently accurate map: